There’s No Way You Listened: Fallacies with Music Journalism

Music journalism has been on the incline since the creation of the Internet. The Internet has allowed for anyone with Wi-Fi access to put out content that they may or may not be well versed in. Unfortunately, for those who study the craft of music and journalism, this can be quite problematic when it’s time to do album reviews. The democratization of the web has made it increasingly difficult for journalists with some level of music credentials to have their voices heard amongst a sea of young suburban men who listen to an album once and suddenly have a handle on what it is the artist is trying to tell them. Journalists are almost required to pump out full-length album reviews after giving the body of work one listen to. Due to the very fleeting nature of the Internet, it's quite difficult for album reviews to live in the digital media space and have any sort of staying power. Media agents don’t get a chance to even wrap their minds around whether or not they truly like a body of work before they have to turn in a comprehensive review complete with a numbered rating. This is to say that the idea of making a judgment on what the reader is to perceive as in disputable fact might just be antiquated. Perhaps it is the job of a music journalist to capture the imagination of its reader by allowing them to first digest a project and present technical observations that would support any claim as to why fundamentally a record was pleasing or not.

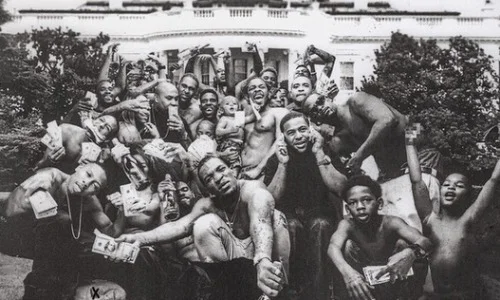

To Pimp A Butterfly Album Cover

Kendrick Lamar shocked the masses when his third full-length project To Pimp A Butterfly leaked on March of 2015, 8 days before the official release date. Upon release, every music blog, podcast, and journalist alike felt the pressure to absorb the record and pump out a review within the first few days of hearing it. Jamieson Cox put out his review in Time Magazine just one day after the release of the project. The critique never delves too heavily into the musicality of the album, however it does note that “while the album’s extreme density warrants plenty of digestion time, it’s apparent from the few listens that it’s worthy of the same sort of praise won by its predecessors, 2012’s Good Kid, M.A.A.D City.” The writer is able to formulate the conclusion that an album that was released just one day prior was worth almost instantaneous praise.

Dead End Hip Hop Roundtable

Dead End Hip Hop, a video blog dedicated to hip hop album review purposefully waits until almost two weeks have passed before they sit down and have a round table discussion about TPAB, opening the video stating that those who hastily reviewed he project “hadn’t actually taken the time to listen to the album and actually live with it.” What a disservice for those who listened, or merely thought about listening to the project seeing the review is being done a day after the leak. Perhaps the bulk of the audience hadn’t gotten the chance to listen to the entire body of work from the opening track to the finale track before a publication like Time has already told them how to feel and what to think about the record. This plants the seed in the listener’s mind that this is a record that they should like if they care about culture, systemic racism, and blackness and the intersectionalities between all three. Imagination is stifled and the listeners never really get a chance to insert themselves into Kendrick’s narrative. The key components of music reviews that one looks at, like musicality, instrumentation, lyrical content is never touched upon in the bulk of Lamar’s reviews as they are so engulfed in its cultural impact that they fail to produce substantial evidence; from Lamar’s flow to his use of heavy jazz instrumentations in these reviews. This leaves the reader misinformed. When an album is as jarring and manic as TPAB one has to ask the question of whether or not the idea of the album review, particularly ones that exist online rob the reader of the chance to become engulfed in a theme, spend time with a record, and allow the record to reveal itself to them.

Lamar put out a body of work so polarizing that Complex Magazine’s Justin Charity reviewed the record not once but twice in which he took two totally different stances. In the original review that was published a day after album release, Charity gave Kendrick 4.5 out of 5 stars stating, “To Pimp A Butterfly is a disembodied outpouring of rage, dread, and irreverence.” He even gets a little technical citing some jazz influencers and making a reference to Spike Lee’s composer, Terrence Blanchard. On November 3rd of 2015 Charity puts out another critique saying that the album was overwhelming and while we cannot deny its impact on culture as a whole, the running theme of blackness and self-discovery is isolating. Charity even references music journalist Rawiya Kameir who felt as if the album’s “overwhelming blackness” made it “critic proof.” This is to say, that according to Kameir the album is only addressed to black people so those who do not fall within that framework need not attempt to review it at all.

These convoluted messages of “the album is good, but not really” or “the album’s cultural significance can be written about a few days after it’s written” or even “the actual musicality of the album is almost irrelevant” puts into question the very validity of album reviews. Kendrick Lamar spent a little over a year working on this project and for a media agent like Justin Charity of Complex to not only write a review a day after he listened to it to only have to turn back around months later to reveal his true feelings about the project merely sheds light on the fallacies of such a method. Music isn’t meant to be reviewed the way in which the likes of media contemporaries like Complex or Pitchfork do the same week the project drops. Music is meant to be lived with. Listened to front to back. Meditated on.

“The inexpressible depth of music,” “so easy to understand and yet so inexplicable, is due to the fact that it reproduces all the emotions of our innermost being, but entirely without reality and remote from its pain…Music only expresses the quintessence of life and its events, never these themselves.” In Musicophilia Oliver Sacks develops this notion that where language fails, music succeeds. Language only has the propensity to tell stories within the confines of letters and vowels and consonants. Music is able to replicate and transfer feeling and emotion from one person to another, allowing for the receiver of that message to use their imagination and play out those feelings in their mind.

Sacks makes the point that a person may “perceive music accurately” but have no sort of emotional attachment to it while someone else may be “passionately moved” by what it is they hear but have no way of properly communicating those feelings with someone else. Lamar’s record recoils feelings of rage and self-loathing and frustration, emotions that are quite difficult to replicate with words. Music reviewers attempt to make sense out of something that “has no concepts, and makes no propositions,” all while trying to satisfy an impractical deadline. When these pieces go out, especially within the week of release, the reviewer is robbed of any chance of actually letting their minds wander and is given no time to actually sit with the records and really dissect the very technical aspects of creating music. Not only are they stifling their imaginations but also they are producing claims with no evidence, skewing the minds of the readers dishonestly.

Perhaps one might find it beneficial if instead of reviewing music as soon as it comes out, particularly in the case of rather dense projects like TPAB, that one let the listener create their own story lines, formulate their own opinions, and in due time the music reviewer may be able to focus on what the record is doing sonically just as much as they are concerned with its cultural impact.

The album did, however, garner Lamar with a whopping 5 grammy awards and 11 nominations and one simply cannot deny the power of attaching "Grammy Award Winning" in front of your album. How important are these arbitrary awards handed out by people so far removed from the art itself? How important is it that a group of your peers validate your art? Is it more important the art itself? Than the lives it touches?

How do you determine whether or not an album is great? Do you read album reviews? Where do you get your music info from? How did you feel about TPAB?

Share in the comments below or tweet us at @wowiwrite