we are all urban planners.

cover image via @newark_arts

“What is urban planning?”

My professor lobbed this question at us on the first day of class. We all looked at each other, “Is he serious?” Of course, we knew what urban planning was. Planning is logistics, politics, design, consultation. These were, of course, the buzzwords we gave him when he pressed us for our answer. He shook his head, “urban planning is making places, plain and simple.”

You see, planning is cross-disciplinary. Very early on into our curriculum, the faculty humbled us. We’re talking about seasoned professionals with decades of experience behind them, yet despite their accolades, they were never the important ones in the room. As a planner, you aren’t the authority, and that’s the beauty of it.

That very professor recounted his time in Trenton, New Jersey as the coordinator of a rehabilitation project. He introduced us to the concept of a community planning process, essentially a design charrette but whose main participants are the residents of the city. The planner’s job is to simply facilitate the methods of planning, whether its through maps, three-dimensional models, or the visual preference survey. Our expertise remains on the backburner, but it should be up to the people to decide their standard of living. This is the essence of planning - democracy. Planning is the toolkit for the people to reclaim their environment.

Newark, NJ

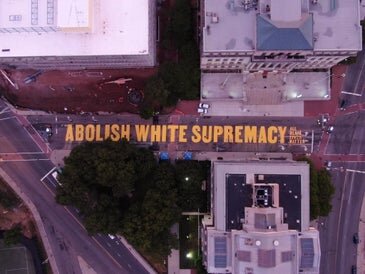

Amid the Black Lives Matter protests after the police murder of George Floyd, demonstrations were taken to the public realm. They made it a point to show the city isn’t the property of bureaucrats, but a home to its many residents that operate as its lifeblood. Organizers drafted proposals to defund their city’s law enforcement and reallocate those funds, often into public infrastructure. Demonstrators took to public school parking lots, streets, city hall, drawing BLM on sidewalks, all of which wasn’t simply performance, but urbanism as a means of activism. A reclamation of public space to echo the public sentiment: to end the injustice on Black and brown people. Of course, we cannot contend with this phenomenon without interrogating planning’s institutionally racist history. As Bryan Lee Jr. iterates in CityLab’s America’s Cities Were Designed to Oppress, “Architecture has been the backdrop and often the instigator for violence on black bodies throughout this nation’s history. This is the case, in large part, because white America has found it all too easy to transpose its capital and beliefs into physical space, allowing the architecture to covertly project power in the name of white supremacy.” It is an indisputable fact that design, especially urban design, is inherently political, and since this country’s conception, it has only reflected the politics of the apparatuses of power. The historic redlining, segregation, gentrification, and lack of access to public services that have deprived Black and brown communities of an adequate standard of living were all deliberate actions at the hands of urban planners. To dictate the future of planning means to reckon with its violent past.

As Lee affirms, “The design profession has a role to play in the short- and long-term outcomes of justice, and we would be wise to revisit our past to find direction.” A call for abolition is not simply a call to end law enforcement and prisons. It’s a call to end the bureaucracy which polices marginalized people through physical space. It’s a demand for residents to reclaim their neighborhoods, and to ensure democracy when designing our cities. For too long, planning has been an instrument of oppression. But if the past few months have taught us anything, it can also be our means to liberation.